As the 21st century has just begun and the destinations that the Russian and the world cultures have reached on the paths of their historical development are being assessed, N.K. Roerich's personality, art, widespread cultural and social activities, the span of his artistic, literary and scholarly creativity seem to stand entirely in a class of their own.

Meanwhile, however, admirers of N.K. Roerich in particular, and people of culture in general remain largely unaware of the meaning of Izvara in the painter's life and creativity. Izvara was his parents' estate where the painter spent 26 years of his life and where he accumulated all the brightest impressions of his childhood and adolescence, which laid foundations to his world outlook and creative assumptions. The inner bond of Nikolay Konstantinovich with Izvara never interrupted over the entire span of the master's life. Multiple lines of evidence to this will be found in his diary, articles and letters. To quote just one of them: 'Everything special, dear and memorable is evoked thinking of the summer time in Izvara'.

For Nikolay Konstantinovich Izvara was 'a cosy nook', his parents' home, a happy world of his childhood and adolescence. The master's love to Izvara, thousands of memories and associations, scattered throughout his 'Diary Leaves' impart to this place a particular status within the vast array of Russian cultural heritage.

'Had not yet been two years of age but had shreds and wisps of memory associated with Izvara, the estate encompassed by woodland 40 versts (70 miles) away from the town of Gatchina' - Nikolay Konstantinovich wrote in the Diary Leave entitled 'The Inception'. As to the origins of the name 'Izvara' there are several possibilities. Some believe the roots to be Finnish: 'iso' – 'large', 'vaara' – 'barrow, mound, hill', i.e. 'a large mountain', or 'iso ( n ) vaara' – 'father mountain' or 'father's mountain'. The association employed here would be that with the multitude of mounds and barrows around the estate.

N.K. Roerich himself believed the name of the estate to have Indian roods, associating it 'with Hindu Išvara' (Sanskrit Ishvara – the Lord, the Most High).

Nature and antiquity surrounded Roerich in Izvara all throughout his childhood and adolescence, it was there that his 'extraordinary way of life', as the painter termed it himself, was being formed. Soon after the sale of the estate in his beautiful article 'To Nature', written in 1901, he would for the first time analyze the inborn yearning of human beings to rejoin nature which is their 'only life's way': 'Everything drives us towards nature: spiritual awareness, aesthetic demands, and our body too …'.

Life's laws were being revealed to young Roerich in Izvara: 'Life in its cultural spiral inevitably draws us towards the primary source of everything'.

It was not only love to nature, but also the urge to learn about the world that Roerich owed to Izvara. He used to gather herbaria, sample local minerals, and when he was 13 years old received a special permit from the local administration to collect eggs all year round in the governmental country estates of the province with a scientific purpose, the result of which was his work: 'Classification of birds of St.Petersburg Province into species, classes, subclasses, and families'. The painter, when young, also wrote stories to be published in 'Russian Hunter's Journal'. Particularly notable is his essay 'Hunting in Tsarskoselsky District', wherein he described in detail the nature and the environment of 'Izvara Woodland Estate'. A notable result of his fascination with hunting was that he had tempered his body and developed great endurance which later determined the success of his Asian expeditions.

It was also in Izvara that Nicholas Roerich began to read books on Russian history.

'In our library in Izvara we had a series of oldish-looking books on the provenance of the Russian Land, a kind of history reader. From my earliest years, as I had developed the ability to read, I came to enjoy those stories' - he wrote. 'There were books about the Battle on the Ice, about Princess Olga and her suppression of the Drevlians, about Yaroslav, and about the Saint Princes and Martyrs Boris and Gleb… There of course was an account of the Battle on the River Kalka, and an adapted Lay of Prince Igor's Host, a description of the Kulikovo Field Battle, Saint Sergiy's valedictory words to Dmitry of Don before the battle, an account of the warrior monks Peresvet and Osliabya. There were stories about Minin and Pozharsky, Peter the First of Russia, Count Suvorov and field Marshall Kutuzov. The covers bore an image of a Russian bogatyr (a mythical warrior) trying to fight off an entire circle of foes with a battle axe. All of that I remembered and it always felt like saying 'Hands off!' when looking at that picture'.

And so it happened that in Izvara the painter's mind conceived an understanding of his country's greatness, the wish to protect its people, a feeling of love and compassion to them: 'what a multitude of undeserved insults the Russian people have suffered …'. His invincible optimism was being moulded at the very same time: '…all that spiteful biting was not of much help to the offenders of the Russian people… the entire variegated crowd of usurpers and aggressors was repelled, whilst the people of Russia was ploughing forth new treasure from virgin soils of their country. That's the way things are...'.

Knowledge of history, many lays and legends preserved by the local people, who lived in a land abounding in ancient monuments, naturally sparked off young boy's interest towards archaeology.

'Around Izvara almost near every settlement there were vast mound fields spanning the period between the 10th and the 14th centuries. Since my early childhood I was attracted to those unusual and uncanny barrows, where captivating ancient metal objects would constantly be unearthed'.

It looked as though fate itself was on his side. At the time a famous archaeologist Ivanovsky was conducting a series of excavations of local mounds: '… this in turn strengthened my wish to know more closely those places of great antiquity'. And so it happened in his childhood that Nicholas Roerich began to take part in archaeological excavations under guidance of an experienced specialist. Young Roerich would donate his first finds to his gymnasium school. 'Over the entire second half of my gymnasium years each summer I would unearth something fascinating '.

Ancient history of Izvara pervaded the realms of the future painter's imagination: 'Around those mounds ancient legends abounded. Folk just would not walk past them at night time. The mound fields, bristling forth with hundreds of barrows kept intriguing silence'.

The realms of Izvara helped him to cognize the sources of great Russian culture.

Archaeology became one of Roerich's most favourite pastimes. Since 1896 he began his co operation with the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society and having become its working member in 1897 started giving lectures, conducting filed excursions and finally professional archaeological excavations leading to a number of discoveries. Until the end of his life Nicholas Roerich remained convinced of archaeology being of great importance in the process of understanding history of human culture. In his milestone article entitled 'Half a Century' the master wrote these momentous words:

'I owe much to you, the mounds of Izvara … Nothing can move one towards perception of antiquity so closely as an excavation performed personally by oneself and what matters in particular is one's first actual tactile examination of an ancient artefact. And if such artefacts are especially close to those historical images which somehow had entered and settled in one's mind of their own accord, then everything becomes ever so closer, inseparable and more convincing'.

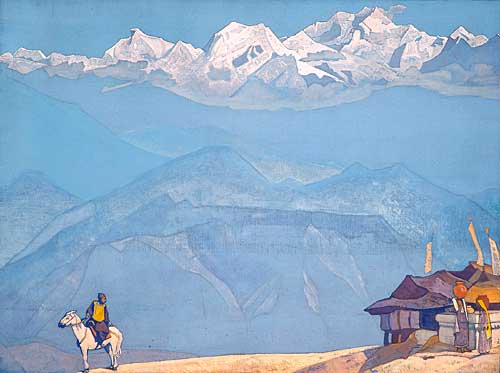

Through the images of Izvara the young painter would venture to fathom the depths of the ancient Rus' with its manifold and diverse cultural influences. It is quite notable that it was in Izvara in the old manor house that N.K. Roerich first time in his childhood saw a painted image of a revered Himalayan summit Kangchenjunga. There were multiple connections with India – the etymological link of the place name through Sanskrit Išvara – the Lord, the Most High, a legend preserved in the family regarding an Indian rajah who allegedly resided near Izvara in the estate of Yablonitsy during the reign of Catherine II. Roerich's deliberations on the roots of the Slavic cultures had led him to suppose that there had been certain interrelation and interpenetration of cultures, he intuited that at some point there must have been an influence of the Orient and of the Indian culture on the culture of old Russia. Later in his paper entitled 'The Indian Way' he would delineate the task of cognizing the Indian culture as being a cultural and spiritual need for the Russians. At the close of his life in the Himalayas Nikolay Konstantinovich wrote in his letter to painter I.E.Grabar:

'Hast thou perchance not heard of a certain curiosity? About 10 versts from our former estate 'Izvara' there was an estate named 'Yablonitsy' where during the reign of Catherine II a certain Hindu rajah used to reside. The informant said to me that he had himself at some point seen the remains of a Mogul park. The late Tagor was highly interested in this fact and was even inquiring whether there might have been any local reminiscences as to the matter … Sometimes we search far and wide but the thing is close at hand. If one looked carefully, then one would see many Russians to have visited India and many Indians to have lived in Russia… But then everything shall be revealed when the time is right, it surely shall!'

In 1893 N. Roerich entered the Law Department of Saint Petersburg University and at the same time the Art Academy.

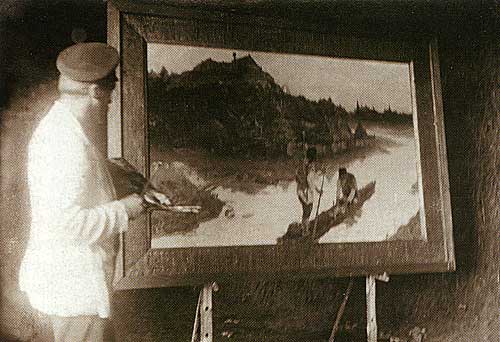

Izvara became his most favourite creative nook, his studio. Below is what the painter wrote: 'The year 1896. The Art Academy. The suite entitled 'The Slavs' is being formed. 'The Messenger. The tribe has risen against tribe', 'The Elders' Moot', 'The Campaign', 'Building the Town' have all been conceived. Stasov has opened the treasure trove of the Public Library. The old hen coop in Izvara has been refashioned into a studio. Wolf and lynx skins have been gathered. Well, the Slavs also need weapons. At the roadside smithy a blackened smith is forging a sword, a real one, steel blade, exactly like we used to unearth in the mounds…'.

Having absorbed the nature images pertaining to this ancient land and its profound past merely by breathing its air, being fraught with faith into the majestic future of his folk, the painter embodies those images in his historical landscapes.

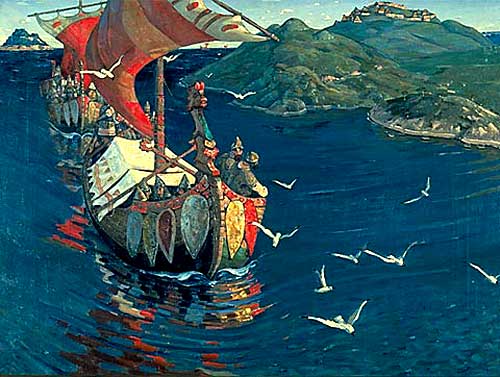

The painter's creations themselves suggest that it was in Izvara that his thoughts about historic destiny of 'the immeasurable Russians' and his position as a citizen of his motherland were conceived. In Izvara he painted among others 'Yaroslavna's Lament', 'Svyatopolk the Evil, 'A Pskovite', 'The Gunners' and 'The Assembly'. 'The Slavic Suite', 'The Kievan Bogatyrs' Evening' (1895-1896) were created – about the resurrection of the bogatyrs, their uprising against the powers of the highest world, against God and about their petrifaction as a consequence. There were also 'The Messenger' (1897) – about the tragedy of feuds fought by the Slavic tribes against one another, 'The Elders' Moot' (1898) and 'The Campaign' (1899). Those early works are reflective of the master's profound deliberations on the reasons for the defeats and the calamities suffered by the Russians incessantly, his speculations about the future. In the words of the master himself from his article entitled 'To the great people of Russia' (1940): 'The messenger of the uprising set out steering his boat forty three years ago. Then the elders gathered – the moot of the burgh. The next year the campaign to protect the motherland was being led high into the mountains. Finally, the town was being built. And along with the building I bow down to the great people of Russia. That is what was being awaited as approaching, such had been the premonition and such was the vision. 'The Elders' Moot' was accompanied by a bylina (an ancient epic), the final words being as follows:

Shall gather a moot at the vast oak, round the branchy tree,

On that tree no ravens rage, on that oak no vultures caw.

Behold, beyond the woods the brave new day breaks bright,

And soon the Scarlet Sun shall shine ablaze

And, aye, again the Russian land shall arise.

'The Bogatyrs Have Awoken' is being painted presently. It's dedicated to the great people of Russia. A bylina was once composed with the name 'On how the bogatyrs became extinct in Rus', but the people composing that bylina believed that the bogatyrs would arise in the predestined hour, shall abandon their caves and take part in the all encompassing building of the people … Nothing frightens the great Russians. All shall be overcome: ice, heat, hunger, and thunderstorm. And, aye, a great deal of building shall commence…' (24 June 1940).

Izvara bore one more significant aspect of family tradition which was of great significance for the painter's world outlook.

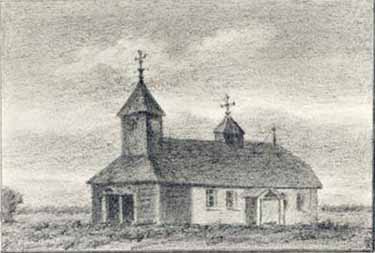

'Two episodes of major importance bring themselves to mind from our family chronicles. A church burnt down near our estate about 55 years back, before the Lent. A dreadful calamity, as the Holy Week and the light-bearing Christ's Festival would have had to be celebrated without a church. To save the local people that holy joy, father warm-heartedly came to heir rescue by donating one of the buildings of his estate complete with the surrounding land, and that building over the six weeks before Easter was transformed into a church through collective labour. A belfry was erected, the icon stand was completed in time, and on Palm Sunday we had the ceremony of lifting the cross and the consecration …'

The other episode was in the time of tsar Peter the First: N.K. Roerich's great grandfather refused to demolish a suburban church during a military campaign 'owing to his profound religious allegiance'.

As N. Roerich wrote: 'Apparently it was due to the family tradition that I also have had to take regular trouble concerning temple construction and preservation of historic sites'.

It should be added at this point that Nicholas Roerich's father's active participation in construction of the temple in close proximity to Izvara was recorded in Statistic Report of St. Petersburg Diocese. Other archive documents also supplemented this story. Amongst the legends collected by N. Roerich in the neighbourhood of the estate, there was one saying that the site for the temple construction in the village Gryzovo had been selected by none other than Peter the First himself, who after one of the battles erected a wooden cross in the vicinity. After the wooden church had been destroyed by the fire, it was decided to reconstruct it in stone on the same spot. N. Roerich was granted a permission to carry out archaeological excavations during the construction works, the results of which were not uninteresting: in the foundation of the temple a big ancient cross was unearthed, only it was not wooden, but made of stone and had two round holes. N. Roerich made a detailed description of the find and sketched it. The origin of the cross is still unknown: it was put back into the place where it had been found in the foundation of the temple, where its secrets are still preserved… The painter's drawings contain images of the church itself and its vicar.

N. Roerich was brought up in the family with profound religious traditions, which he took over during his childhood. According to the historical documents the water springs in Izvara were blessed at Epiphany. It was Maria Vasilievna – Nicholas Roerich's mother – who invited the priest. Thanks to her, N. Roerich from his early years had a possibility to meet Ioann of Kronstadt, who was Maria Vasilievna's confessor. Even during his lifetime father Ioann became famous for his numerous wonders and miraculous healings. There are many records testifying that even people of different believes asked for his help. Once father Ioann thus addressed Nicholas Roerich: 'Do not get ill! You will have to work hard for your country.'

Thus love, knowledge and art, worshiping the Divine Principle of life merged in N.K. Roerich's mind when he comprehended the world during his childhood and adolescence in Izvara.

Life led him to seeing the synthesis of religion, science and art as the greatest principle of culture, the principle of the new era, the harbinger of which N.K. Roerich was destined to become.

At the graduation exhibition of the Academy of Art 'The Messenger' was purchased by Pavel Tretyakov. Nicholas Roerich established himself a reputation. His essays were being published in newspapers and journals, his works were being spoken of and discussed, he continued his activity as an acknowledged archaeologist, he also was invited to join the 'Society for the Encouragement of the Arts'. But in 1900 his father died…

Izvara estate was sold. The money was used to pay for N. Roerich's studies in France…

This was the beginning of the new period of his life, but at the same time everything conceived in Izvara did not cease and continued to develop. Youth, craving for perfection, longing to prove his right for the chosen path in life, the meeting with Elena Ivanovna Shaposhnikova and the following marriage assuaged the pain of the parting with his dear Izvara. Besides, he still lived in Russia, in St. Petersburg, very close to his former estate. There are some records proving that Nikolay Konstantinovich used to bring his sons to Izvara to show them his former home.

And only in 1918 the moment of farewell came when owing to the circumstances the Roerichs found themselves abroad – in Finland that had just became independent…

A difficult Journey routed by his heart lay before him, the parting with his motherland… and it was at that moment that he expressed his farewell to Izvara in the following poem:

All that was mine I renounced.

You will take it, my friends…

But once more—for the

Last time I shall survey all that

Without any doubt, the formation of Nikolay Konstantinovich's personality was conditioned by many factors: his parents' and relatives' influence, K.I. May's gymnasium, his father's friends, among whom were historians, oriental scholars, scientists and artists and many more.

We would like to note that many aspects of this process came from Izvara and 'everything special, dear and memorable' for Nicholas Roerich was connected with this place. Izvara helped him to understand, to feel the only way leading to the summits of the Spirit, which Nikolay Konstantinovich left for us in his 'Testament':

'Love your Motherland. Love Russian people. Love all peoples who inhabit the vast territories of our Motherland. And let this love teach you to love all mankind. To love your Motherland you must know and understand it…'